What artists know when the world burns

This edition of art | earth | consciousness is dedicated to the field of possibility.

It's a challenging time to write about love, hope, and beauty.

It's difficult to remember a time when suffering was more widespread or of greater magnitude. In times of darkness, we reach for hope and we lean on the faith that something more beautiful is yet to come.

Why Creative Courage Matters More Than Ever

You likely know CS Lewis for his children’s book series “The Chronicles of Narnia". Like me, you might have also seen his quotes about war circulating on social media recently:

"If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things: praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs."

But there's something remarkable about Lewis that most people don't know.

CS Lewis: The Wartime Creative

While horrified by war (having been wounded serving in WWI), Lewis rallied to support his countrymen during WWII's darkest hours. Beyond holding his Oxford professorship, he simultaneously served in the Home Guard, conducted BBC radio broadcasts during air raids, became the first President of the Oxford Socratic Club, and visited RAF stations on summer weekends to boost troop morale.

Here's the extraordinary part: Lewis's creative output during the war years represented a 630% increase in productivity compared to his normal pace. He published 11 major works in 6 years while bombs fell on London, transforming from respected academic into the voice of faith for an embattled nation.

Pre-War Period (1919-1938): 5 works over 20 years

War Period (1939-1945): 11 works over 7 years

Post-War Period (1947-1961): 17 works over 15 years

Sari Shryack: Art as Cultural X-Ray Vision

While deep in my CS Lewis research, I came across a Threads post by Sari Shryack that perfectly captured what I was discovering. The Austin-based artist and art teacher had been reading JF Martel's book "Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice" and reflecting on art's role during difficult times:

This quote is Sari’s monologue from the video:

"There's a great Groucho Marx quote that says 'I'm not crazy about reality, but it's still the only place to get a decent meal.' This quote often makes me think about the relationship between art and reality. When the world feels like it's burning, art can seem like an escape at its best, a place for people to catch their breath, and at its worst, an ostrich sticking its head in the sand. But I think this does a disservice to the truth that art can reveal. It gives us a wider lens, almost like x-ray vision, into the heart of culture, its values, and contradictions... I suspect that it's at times that art feels the most small and indulgent is exactly when we need it the most."

JF Martel: Art as Vital Defense

Inspired by Shryack's post, I dove into Martel's book. His argument is compelling: authentic art is necessary to push back against our world saturated by consumerism, artificiality, and mass media. True art "disrupts the ordinary, opening a 'rift' in our perception and revealing new ways of being." Martel positions art as vital defense against manipulative forces, not escape from reality, but deeper engagement with what's real.

Art As Antidote

In our current environment, art isn't distraction. It's the antidote. When the world feels like it's burning, creativity becomes both refuge and resistance, both personal medicine and collective healing.

the birds: Royal Spoonbill

Spoonbills follow water, which makes perfect sense, their natural habitat is wetlands.

Here's the surprising part, they don't migrate based on actual rainfall. Instead, these magnificent waterbirds detect changes in barometric pressure thousands of kilometres away. Flying on faith that rain is coming and soon the runoff will soon create wetlands bustling with life.

The enigmatic nature of Spoonbills doesn’t end there.

Their distinctive spoon-shaped beaks allow them to feed on faith too. Wading in wetland margins, in murky water with bills oscillating side to side, seeking nutrition they can't see, but feel through specialised nerve endings. Using tiny sensors (Herbst corpuscles) in their bills, spoonbills detect pressure changes as tiny as 0.001 mm of water displacement, a sign they've found sustenance.

Spoonbills live in community, beginning their feeding process spread out to improve the possibility that one of the flock will find a meal.

When seeking food, their dance-like motion sweeps at 20+ times per minute. But when they discover abundance, their dance slows to 12-15 sweeps per minute, signalling to other spoonbills that they've found a rich vein of food. The flock comes together to feed as a group.

I've always thought of wetlands as temporary autonomous zones like a rave or a “bush door” where all kinds of organisms bloom in celebration of life.

Royal Spoonbills (Platalea Regia) serve as umbrella species for wetland conservation. They are living barometers of hydrological health, their presence, an indicator of thriving aquatic food webs and their absence signalling ecosystem stress.

Spoonbills As A Symbol Of Community Health

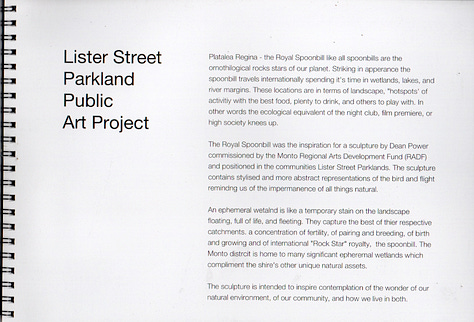

In 2001, my hometown of Monto in Queensland, was suffering from dairy industry deregulation and new regional forestry agreements.

Two of our most significant industries were severely impacted. Our dairy factory closed, workers were laid off, and as we began questioning our identity: "Are we still a dairy town?”, “Should we still celebrate our Dairy Festival?”

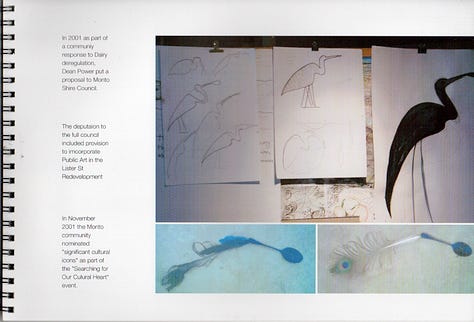

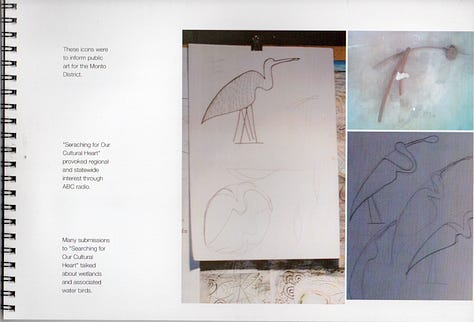

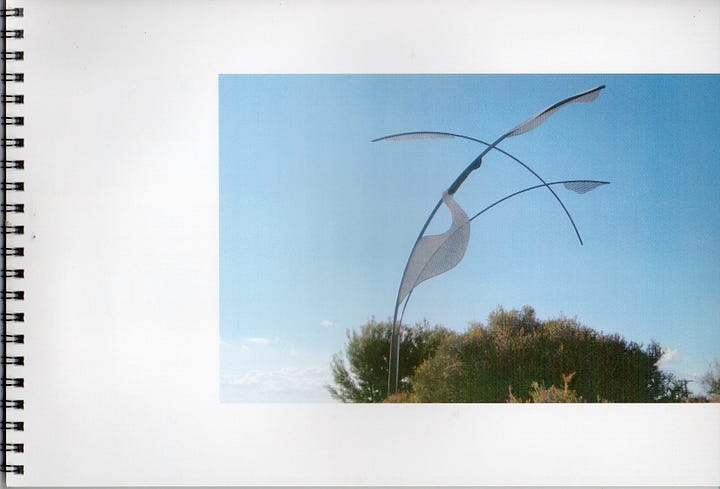

In response, I proposed a public art project to our local government and community to reinforce the timeless elements of our rural community. After council approval, I was commissioned to create a 5-metre metal spoonbill sculpture. During a cultural mapping exercise, the community identified our regionally significant ephemeral wetlands, natural festivals celebrating the abundance of bird life, including the arrival of spoonbills. I choose the Spoonbill because to me it represented the abundant life-force that persisted beyond the whims of government and industry.

Little did I realise at that time that the Spoonbill was such a perfect metaphor for having faith that nourishment would come and that our community would come together to strengthen the health of our district.

Spoonbill Sculpture Project Outcome Booklet

Rather fittingly, after the public opening of the sculpture, Monto experienced a period of somewhat unseasonal and much-needed rainfall.

the birds: is a series of essays about birds that have inspired my life and art

01 Splendid Fairy Wren | 02 Kookaburra | 03 Spoonbill | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09

How To Create When You're In Sticky Emotions

Feeling creatively stuck is completely normal, it's as natural as the urge to create itself.

In any creatively lived life, feeling stuck will happen repeatedly. Often in times of stress and unexpected change. But here's the gift: it's a moment to be grateful for having creativity at all. When emotions overwhelm us because of things beyond our control, creativity brings us back to something we do have control over: what we create.

Here's a process I've found helpful:

1. Start with gratitude

I journal gratitude by hand, because handwriting activates neural pathways in ways that thinking alone or typing cannot. This simple act shifts your brain from fight-or-flight into creative receptivity. Start with the simple enquiry what am I grateful for? This will be your first act of creativity, however it’s really just primping the pump.

2. What's one small step?

If you have a creative project in progress, ask: "What's the smallest step I can take to move this forward?"

If it's a painting, maybe clean your brushes. If it's sewing, pull patterns from your drawer or thread a needle. Maybe you have a half-finished project gathering dust. Pull those pieces out, dust them off, and figure out the next tiny step.

If you don't have a project, start the smallest, simplest thing possible. Doodle on old envelopes. Draw whatever's on your kitchen table. Start free-writing. Anything that gets your hands moving.

I like to say: "When my hands start moving, the muse appears."

3. Celebrate that shift

Just like the Spoonbill starts dancing when it finds food, express gratitude for the creative shift you feel happening. You don’t need to throw a dinner party (but you can), simply recognising the change that you’re feeling is the key. If you make part of your celebration sharing with others. Then like the Spoonbills, your good is shared with your community.

Journal Prompts:

I feel grateful for... (write at least 4 things, keep going if you're on a roll)

What's the smallest step I can take on a creative project? (list at least 3, pick the easiest)

Poetry: What If?

“What if you slept?

And what if, in your sleep, you dreamed?

And what if, in your dream, you went to heaven and there plucked a strange and beautiful flower?

And what if, when you awoke, you had the flower in your hand?

Ah, what then?”

Samuel Taylor Coleridge - from his unpublished Notebook Entry

Connection Heals

A heart that holds only hate and fear grows isolated. But love, even small acts of it, creates connection that can bear us through the heaviest times.

Having had the privilege of working in Natural Resource Management I have seen ecosystems respond to connectivity. You may have experienced this in your own life, when we before isolated from the good people around us, well-being begins to suffer. We humans heal the way nature heals through connection and creativity.

Create And Connect

This has been a trying week, personally and collectively. This might be the hardest newsletter I've had to write. But the creative act of writing this edition has reminded me of CS Lewis and his extraordinary response to the suffering he witnessed around him. The spoonbill reminded me that it's natural to have faith that a more beautiful world exists if we all come together and create it.

Our creative courage isn't about waiting for better times—it's available to us right now to create beauty when what we see around us feels ugly.

Finally, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's transcendent dreaming asks: "What if?"

What kind of world can we create when we have the courage to lean into the field of possibility?

Faith. And hope. That’s the hardest thing, isn’t it? I’ve been stuck in my own head and in my news/substack feed way too much lately. I have a LOT to say but whenever I sit down to say it, what comes out feels … inadequate.Dull. Incriminating. So much suffering, and so many who seem truly thrilled to inflict it. But … It gives me hope to read things by people who are thinking deeply about love and art and faith and empathy. Connection. Humanity.